Because my family settled in Northeast China before relocating to the Korean Peninsula, I am now a fourth-generation Chinese immigrant in North Korea. During the early years of the Republic of China, many Chinese migrated to Korea due to the turbulent East Asian political landscape, forming a community of Chinese expatriates. In North Korea, the Chinese community was positioned below Japanese and North Korean residents but still managed to establish roots locally. By sharing my personal experiences, I hope to help more people understand the reality of Chinese expatriates in North Korea.

Hey there, I’m a Chinese expatriate born in North Korea. Today, I’d like to share with you why I was born there and give you a quick overview of the Chinese expatriate community in North Korea.

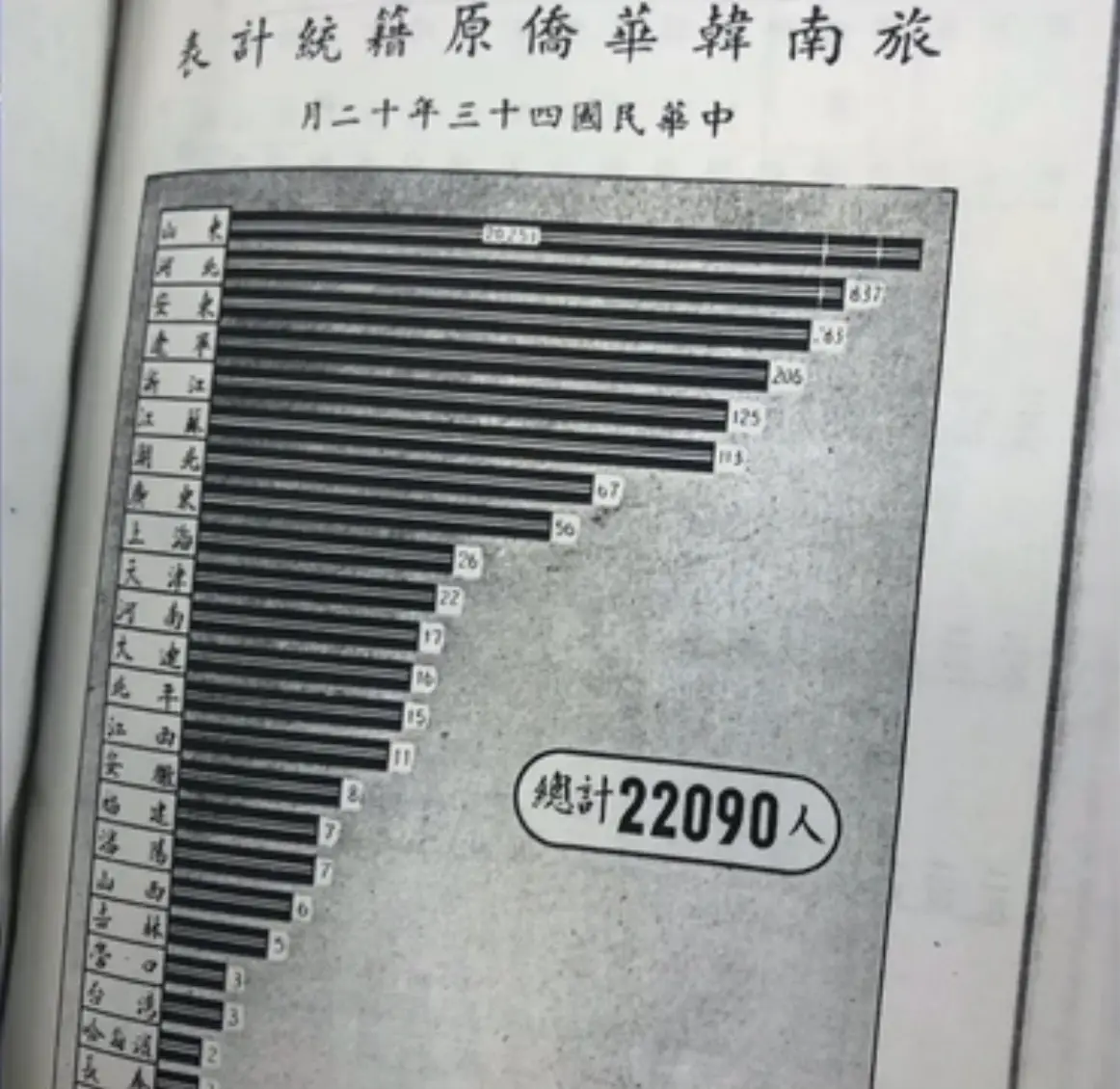

In the early days of the Republic of China, roughly from 1912 to the 1920s, China was still in the early stages of political turmoil and development. East Asia as a whole was in turmoil, so border crossings went largely unnoticed. In fact, most of China’s Korean compatriots were early immigrants from that time, and the vast majority of overseas Chinese were Shandong people who ventured into Northeast China, with some traveling even further to the Korean Peninsula. At that time, my great-grandfather, as the eldest son in a large family, came to Hamgyong-do in Korea in 1921, which was the tenth year of the Republic of China. Back then, the Korean Peninsula was still one country, and Hamgyong-do was not yet divided into North and South. My maternal grandmother’s parents, on the other hand, took a boat to Incheon and, by chance, also settled in a small city in Hamgyong-do, where they opened a Chinese restaurant. This was during the Japanese colonial period on the Korean Peninsula. My great-grandparents and my maternal grandmother’s parents both settled and established their lives in Korea. My maternal grandfather arrived in Korea during the special period of the 1960s. Tracing back to my great-grandfather, we are the fourth generation of Chinese in Korea, and likely the last generation of overseas Chinese residing there. According to the records of the Korean Chinese Chronicles, before the division, the total number of Chinese on the peninsula was over fifty thousand people.

During the Japanese colonial era, as my grandmother recounted, there was a clear social hierarchy: the Japanese were at the top, the Koreans in the middle, and the Chinese living in Korea at the bottom. As a result, the Japanese were secretly referred to as ‘devils,’ and the Koreans as ‘bamja’ (sticks). However, once Koreans realized that ‘bamja’ was derogatory, the older Chinese immigrants began calling them ‘horizontal gnawers’ instead—a term for corn, referencing how corn is eaten horizontally. After enduring the Japanese colonial period, the Korean Peninsula was torn by civil war. My grandmother, along with her two sisters, huddled in a rice paddy to escape bombings from both sides. The aftermath of the Korean War (1950-1953) left the peninsula divided, separating families across the border, and the Chinese community was also split. Those in the north came under the jurisdiction of the People’s Republic of China, and over time, the terms ‘North Korean Chinese’ and ‘South Korean Chinese’ emerged to distinguish between the two groups. In the following years, some Chinese volunteers stayed behind in North Korea, with a few others arriving later. However, as more overseas Chinese returned to settle in their homeland during the 1990s, the number of Chinese residing in Korea dwindled. It is said that the older generation of Chinese held certain prejudices against new arrivals, and there was also widespread discrimination against mixed-blood children, who were often referred to as ‘Jia Gu Bai’.

After the armistice between North and South Korea, Chinese immigrants in Korea received national treatment, and at times even privileged treatment, allowing them to receive extra rations. However, despite being Chinese, they still faced restrictions when attempting to return to their homeland. Later, as relations between the two countries soured, some Chinese immigrants, under pressure from the authorities, felt compelled to “voluntarily” give up their Chinese nationality. According to my grandparents and great-grandparents, when they saw the words “voluntarily giving up Chinese nationality” on the documents, their hearts trembled with fear, but they held their ground and refused to sign. As time went on and the supply system collapsed, Chinese immigrants leveraged their unique ability to travel freely between the two countries to start small businesses. They bought large quantities of goods, particularly hair dye, repackaging it into smaller portions—a practice colloquially known as “selling colors”—to make a living. They also engaged in cross-border trade, bringing Japanese Omega watches owned by Japanese returnees in Korea to China, and taking Chinese furniture and electronics to Korea. Essentially, they were early cross-border traders. Some Chinese immigrants thrived in their business ventures, transporting large volumes of goods, and some even became involved in gray-market activities prohibited locally. Their experiences were marked by both successes and hardships as they navigated the complex life between two countries.

Due to their long residence in North Korea, even with two Chinese schools, the Chinese language proficiency of the overseas Chinese community has gradually declined. Most third-generation overseas Chinese speak a Shandong-accented version of Chinese in a Korean style. Among them, those with strong academic performance were sent to study in Guangdong and Fujian under national policies, where many remained. For those who did not attend university, a trend emerged of sending their children to study in border cities. Since the early 2000s, many families began sending their children to schools in border cities. However, life posed numerous challenges without household registration. In recent years, many families have gradually returned to settle in their homeland. It is believed that in a few decades, the overseas Chinese community in North Korea may cease to exist.

It’s truly regrettable that the history of the Korean-Chinese community has gone undocumented, especially compared to the well-documented histories of Chinese communities in Southeast Asia and South Korea. Since the 1950s, there has been no one to systematically record the history of the Korean-Chinese community. It saddens me to think that when my grandparents’ generation is gone, no one will be left to recount where we Korean-Chinese came from and how we survived through the cracks of history.